Villa Road, Brixton, was once one of the UK’s most famous squatted streets; many of the houses that remain in the road today are part of housing co-ops which trace their origin to the squats of the 1970s.

Brixton, late 1960s: A century and a half of social change had transformed a prosperous suburb into a mainly working class area. Much of the old Victorian housing had been sub-divided and multiply occupied, and was in a state of disrepair and over crowding.

In response the local Planners came up with a massive crash programme of redevelopment; of which the Brixton Plan was the central plank.

The Brixton Plan was also partly a response to the GLC approach, in the late 1960s, to the newly merged/enlarged boroughs, asking them to draw up community plans, to redevelop local areas in line with the GLC’s overall strategy for “taking the metropolis gleaming into the seventies”. Lambeth planners came up with a grandiose vision for Brixton, typical of the macro-planning of the era, which would have seen the area outstrip Croydon as a megalomaniac planners’ high-rise playground. The town centre would have been completely rebuilt, with a huge transport complex uniting the tube and overland railway station, Brixton Road redesigned as a 6-lane highway, (part of Coldharbour Lane was to have been turned into an urban motorway under the Ringway plans…)

Lambeth had already obtained Compulsory Purchase Orders (CPOs) on areas to be redeveloped – all over the Borough large-scale demolitions were scheduled for replacement by estates. The Brixton Plan called for houses in the Angell Town area, now covered by Angell Town Estate, Villa Road and Max Roach Park, to be removed.

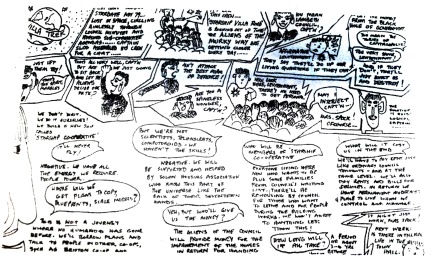

All over the Borough CPOs were imposed, and indeed resisted by many local groups that sprang up to try  and inject some sense into the plans. Blight and decline tend to become a vicious circle, especially in housing. They pointed out that many of the houses marked for demolition were not run down, and had plenty of life in them, that there’d be no Housing Gain (a bureaucratic term for how many more people would be housed after redevelopment than before), and that complex existing communities would be destroyed. The active opposition to Compulsory Purchase and demolition often came from owner-occupiers, who supposedly had ‘a greater stake’ in the houses, although in most CPO areas tenants outnumbered them 2 to 1… But most campaigns were aware of the danger of becoming just a middle class pressure group and attempted to involve tenants as well. Planning processes ignored tenants: only the objections of owner-occupiers or those who paid rent less often than once a month were allowed in any Planning Inquiries. But alternative plans were drawn up to include tenants co-operatives/take-over by Housing Associations as well as owner-occupancy instead of destruction. The Council of course, feeling as ever that it knew best, tended to treat residents objections and proposals with contempt or indifference. Its policy was to split tenants from owner-occupiers in these groups, presenting the owners as fighting only for their own interests, and offering tenants a rosy future in the new estates… they also, as you’d expect, tried to keep these groups and others in the dark about planning decisions. Where the Council owned or acquired houses, the inhabitants, many in sub-divided multi-occupancy, were promised rehousing (eventually, for some); but imminent demolition meant Lambeth spent little effort following up needed repairs and maintenance, tenants became frustrated and pushed for immediate rehousing.

and inject some sense into the plans. Blight and decline tend to become a vicious circle, especially in housing. They pointed out that many of the houses marked for demolition were not run down, and had plenty of life in them, that there’d be no Housing Gain (a bureaucratic term for how many more people would be housed after redevelopment than before), and that complex existing communities would be destroyed. The active opposition to Compulsory Purchase and demolition often came from owner-occupiers, who supposedly had ‘a greater stake’ in the houses, although in most CPO areas tenants outnumbered them 2 to 1… But most campaigns were aware of the danger of becoming just a middle class pressure group and attempted to involve tenants as well. Planning processes ignored tenants: only the objections of owner-occupiers or those who paid rent less often than once a month were allowed in any Planning Inquiries. But alternative plans were drawn up to include tenants co-operatives/take-over by Housing Associations as well as owner-occupancy instead of destruction. The Council of course, feeling as ever that it knew best, tended to treat residents objections and proposals with contempt or indifference. Its policy was to split tenants from owner-occupiers in these groups, presenting the owners as fighting only for their own interests, and offering tenants a rosy future in the new estates… they also, as you’d expect, tried to keep these groups and others in the dark about planning decisions. Where the Council owned or acquired houses, the inhabitants, many in sub-divided multi-occupancy, were promised rehousing (eventually, for some); but imminent demolition meant Lambeth spent little effort following up needed repairs and maintenance, tenants became frustrated and pushed for immediate rehousing.

Lambeth’s planning dream however, quickly turned into a nightmare, with a tighter economic climate and the end of the speculative building boom of the 60s. Much of the Brixton Plan was being cut back: the government refused to fund the Town Centre Development in 1968, as it would have taken up 10% of the total town centre development fund for the UK! The five huge towers, the six-lane dual carriageway, the vast concrete shopping centre and the urban motorway never materialised, and companies involved ran out of cash and ran to the Council for more (eg Tarmac on the Recreation Centre). The building of new housing slowed down. The Council had aimed at 1000 new homes a year for 1971-8 – this target was never met.

By the early 70s much of Central Brixton was in a depressed state. Many houses were being decanted, but for many reasons, large numbers of the residents found themselves ineligible for rehousing; one reason was the overcrowded state of many of the dwellings, with extended families, sub-letting, live-in landlords, etc: many people were not officially registered as living there, and so council estimates of numbers to be rehoused or the ‘housing gain’ were often wildly inaccurate.

Homelessness was on the rise. Two main results of all this were a rapid increase in the number of squatters in the area, and an upsurge in community, radical and libertarian politics in the Borough. Villa Road became a centre of both.

Squatters were increasingly becoming a thorn in the Council’s side. Dissatisfaction with Lambeth’s planning processes and its inability to cope with housing and homelessness gave focus to a number of dissenting community-based groups. Activists in these groups were instrumental in establishing a strong squatting movement for single people – the main section of Lambeth’s population whose housing needs went unrecognised. Many had previous experience of squatting either in Lambeth or in other London boroughs where councils were starting to clamp down on squatters, reinforcing the pool of experience, skill and political solidarity. The fact that a certain number of people came from outside Lambeth was frequently used in anti-squatting propaganda. In response to Council tirades on squatting, squatters’ propaganda focused on Lambeth’s part in homelessness, what with the CPOs, refusal to renovate empties, insistence on buying houses with vacant possession, its habit of forgetting houses, taking back ones it had licenced out. They pointed out that many of the squatters would have been in Bed & Breakfast or temporary accommodation if they weren’t squatting – many in fact HAD been for months (in some cases years) before losing patience and squatting.

Squatters were increasingly becoming a thorn in the Council’s side. Dissatisfaction with Lambeth’s planning processes and its inability to cope with housing and homelessness gave focus to a number of dissenting community-based groups. Activists in these groups were instrumental in establishing a strong squatting movement for single people – the main section of Lambeth’s population whose housing needs went unrecognised. Many had previous experience of squatting either in Lambeth or in other London boroughs where councils were starting to clamp down on squatters, reinforcing the pool of experience, skill and political solidarity. The fact that a certain number of people came from outside Lambeth was frequently used in anti-squatting propaganda. In response to Council tirades on squatting, squatters’ propaganda focused on Lambeth’s part in homelessness, what with the CPOs, refusal to renovate empties, insistence on buying houses with vacant possession, its habit of forgetting houses, taking back ones it had licenced out. They pointed out that many of the squatters would have been in Bed & Breakfast or temporary accommodation if they weren’t squatting – many in fact HAD been for months (in some cases years) before losing patience and squatting.

A strong anti-squatter consensus began to emerge in the Council, particularly after the 1974 council elections. The new Chair of the Housing Committee and his Deputy were in the forefront of this opposition to squatters, loudly blaming them for increased homelessness. Councillor Alfred Mulley referred to squatted Rectory Gardens as being “like a filthy dirty back alley in Naples.”

Their proposals for ending the ‘squatting problem’, far from dealing with the root causes of homelessness, merely attempted to erase symptoms and met with little success. In autumn 1974 All Lambeth Squatters formed, a militant body representing many of the borough’s squatters. It mobilised 600 people to a major public meeting at the Town Hall in December 1974 to protest at the Council’s proposals to end ‘unofficial’ squatting in its property.

Most of the impetus for All-Lambeth Squatters came from two main squatting groups – one in and around Villa Road, the other at St Agnes Place in Kennington Park.

In parallel many tenants and other residents were organising in community campaigns around housing, like the St Johns Street Group around St John’s Crescent and Villa Road… Direct action against the Council by groups like this led to tenants being moved out, the resulting empties being either trashed, to make them unusable, squatted, or licensed to shortlife housing groups like Lambeth Self-Help. Tenants’ groups in some cases co-operated with squatters occupying empties in streets being run down or facing decline.

Following the failure of the Council’s 1974 initiative to bring squatting under control, the Council tried again. It published a policy proposing a ‘final solution’ to the twin ‘problems’ of homelessness and squatting. It combined measures aimed at discouraging homeless people from applying to the Council for housing, like tighter definitions of who would be accepted and higher hostel fees, with a rehash of the same old anti-squatting ploys like more gutting of empties. The policy was eventually passed in April 1976 after considerable opposition both within Norwood Labour Party (stronghold of the ‘New Left’) and from homeless people and squatters.

Villa Road, and later St Agnes Place, were to be the main testing grounds for this new policy.

In Villa Road, just north of Brixton’s town centre, empty houses cleared for the Brixton Towers plan had been gradually squatted between 1973 and 1976. The houses had in many cases been gutted or smashed up by the council as they became empty, or had been squatted, to be rendered totally unliveable in, in an attempt to deter squatters from moving in or staying. This was a policy used across the borough. In some cases this got highly dangerous: squatted houses in Wiltshire Road (which adjoins Villa Road) were smashed with a wrecking ball while an old woman was still living in the neighbouring basement, while squatters were out shopping (puts a new slant on that old chestnut about squatters breaking into your house while you’re down the shops eh, after all this time we find out that it was the COUNCIL!). There was said to be a secret dirty tricks committee in Lambeth Housing Department thinking up demolition plans and ordering them done on the sly.

However sabotage of houses didn’t deter people moving into Villa Road:

“We would go along perhaps late at night and get in the houses and get the electricity sorted out and then help the people to clear out the houses and make them habitable really. When we moved into the houses, they had had council wreckers in them who had broken a lot of the fabric of the houses. They broke the toilets and they poured concrete down them. The broke a lot of the windows, they tore up floorboards and pulled down ceilings. And we all set to fix them, and when I look back on it, the sort of things we did were quite astounding. Because they had poured concrete down the drains, it meant that you had to dig up the connection to the main sewers out in the street. We just used to dig up the whole lot and connect it up to the mains. What do you remember about that house, 39, when you got there?

-How terribly filthy… it was, and…

-No floorboards…

-No, no floorboards.

-There was an old guy who had shell-shock, caught him living there.

-That’s right.

-The basement was full of excrement,

-because he had mental health problems.

-It needed a lot of cleaning up. We went out skipping

– skipping was going round and looking in the skips that were on the streets and… collecting whatever it was you needed. So that was, you know… There were two activities, skipping and wooding. Wooding was going out and reclaiming all the wood from the houses that were being demolished, and, you know, you basically built your environment. In winter, the ice was on the inside of the windows. Heating was like one bar, one of those long fires mainly for bathrooms, I think. We used to cook on that as well, beans on toast – total fire hazard. The wiring was totally bent and, you know, illegal, the gas was. It was, you know… I remember seeing a huge rat coming up from the basement at one time. Yeah, it was pretty rough.”

As houses were slowly renovated, Villa Road became home to several hundred people, residents who created lots of alternative projects: An informal economy evolved, though partly subsidised by the various DHSS giro payments of residents (some of who used to drive the van the good quarter mile to the dole office or post office to sign on or cash in, by some accounts!) The communal arrangements included a food co-op, (based on vegetables skipped from New Covent Garden market in Nine Elms), a ‘pay what you can’ street café, a medical service run by Patrick and Maureen Day, who were both qualified GPs (‘Check up for

the price of a smoke’, and an adventure playground for kids A women’s group formed c.1975-6; a musical collective was set up around the same time (at least 3 bands formed here too) The street had its own newspaper, the Villain, edited by squatting activist (and now transport guru, cycling advocate, and Labour Party politician) Christian Wollmar…

As with elsewhere in the squatting movement of the late ’60s and early ’70s, there was a mix of people from a variety of backgrounds, though a core of the original group that kicked of the occupation of the street included a number of white, middle class graduates, some of who had been to Oxford and Cambridge universities. Politically, there was an early contingent from left groups like the International Marxist Group, though spiced with a typically 70s hotchpotch of new age therapies and, er, cults…

No 31 Villa Road, was, for a while, the base for the more IMG-oriented types.

“There were two influences on us. One was obviously Marx. We were Marxists, we saw ourselves as Marxists. We were in things like Marxist reading groups and we studied Marx. But we were also influenced by people like Laing and Cooper and were into the death of the nuclear family. This rejection of the nuclear family was born of an intellectual analysis which saw the family as an essential unit of a capitalist society. We felt it was necessary – or should be possible – to have supportive, economically viable, emotionally rewarding relationships, familial sexual relationships, with people without creating, or commodifying as we like to call it, commodifying the family unit. We had a lot of theories around the family unit being the building block of capitalism. These beliefs made life complicated at the squatters’ resource centre that Paul helped to run. If people within a sexual relationship had or wanted… to have an intimate physical relationship, whether it was sexual or not, with other people, then that had to be acknowledged and it had to both be acknowledged by both partners, but also allowed to happen. It was agonising, because you were supposed to say it before you do it, not just come back and say, “Oh, by the way, I’ve bonked Bill.” You would…have to explore the feelings you had, the pressures – emotional and sexual – on you and the other person with the group or with the people it directly impacted on before you did the deed. I mean, I don’t know anybody who like thought they want to get married. I certainly didn’t think I wanted to get married and I consider myself proud never to have got married. And it is quite different again now, but, yeah, I mean, nuclear family… a lot of us had come from pretty unpleasant nuclear families. And that does open up ideas for how you might live. It seemed that the nuclear family was really in crisis. And…you know, the idea of a stable couple having children was not really part of most people’s experience in that particular kind of sub society, you know. And it also implied a degree of isolation from others. I mean, there was a great collectivist vibe at that time. How you live together was very much open to question, and I think we…partly just out of necessity, but we tended to live in communes, and that seemed as if that was the way that that could work more generally in society.”

No 12, however, became the base for the ‘Primal screamers’… Jenny James was a follower of both communist sexologist Wilhelm Reich, and Californian psychotherapist Arthur Janov, who had developed a therapy known as primal scream, in the course of which patients relived the trauma of their own birth.

Despite having no formal training, Jenny set up a primal therapy commune in Donegal in Ireland. At the same time, she established a sister commune in a squat at number 12 Villa Road.

“The idea was that therapy should not be the preserve of the moneyed bourgeoisie, but should be available free of charge to anybody. I was called the black sheep of the… Oh, I’d brought the therapy movement into disrepute. This came from the big, posh therapy centres. What it boiled down to was I wasn’t asking money. Anyone can do therapy if they go through things themselves. They don’t need some posh training. It was just a question of human empathy and, of course, knowing yourself really well, being honest with yourself. And so I just opened the doors. It was primal scream and it did involve…screaming. Letting… Which was… Sorry, I’m not laughing at that. It was very genuinely felt. It was about letting out your inner anguish. Um, it was noisy. SHE SCREAMS That’s what I say to you! Ah…! It is extremely organic and well worked out. Nothing’s false. It is something that comes out. When things do really come out from very far down in the body, they can sound quite animal-like.”

“They can be quite scary. What wasn’t nice was that they were all naked while they were doing it. When you’re six, and there’s a big group of people rolling round the floor naked, you’re thinking, “What is going on here?” There was my friend’s mum – she was the one that did it – Babs. You just think, “It’s so strange,” cos you’re playing out in the garden, you pop in for a drink, and someone’s in the kitchen naked.”

“Our one-to-one sessions were extraordinary and incredibly valuable. I wouldn’t ever regret any of that or want it to be any different. Um, but the downside was the group. Living… The thing was, we’re all there, we’re all feeling really vulnerable. We’re all looking for ourselves. We’re all looking for friends and support and home and family and answers. So everybody was vulnerable and everybody was at different stages of this exploration, this journey. And there was no account taken of that in any structured way or in any way really. Throughout the years, what would happen is, now and then, some of the stronger characters would actually cross the metaphorical line. They’d cross the line, come in, get involved. We had a lot of lovely-looking women in our commune. -They’d form relationships. They’d start to look at it.

-So was that what drew them in?

-The women?

-I would say that was probably obviously a first hook, if you like. But then they’d see and it was very interesting what we do. They’d see that and they’d see that it worked. They’d get interested. It was a deeper way of living. I remember that, um, the primal screamers… The story was… I think it was probably true, too. ..that the primal screamers sort of sent vixens out onto the street to seduce the handsome boys who were on the left, and to get them to scream instead of, you know, agitate or something. I don’t think it was that organised. It sounds a bit of a conspiracy theory to me.

– You weren’t lured in by a woman?

– I was lured in by a woman, actually. So, you never know, do you? I don’t think she was acting on orders. I think she just fancied me. It always reminded me of that film, The Invasion Of The Body Snatchers, in that one would wake up and discover that somebody else from the street had been captured by the primal scream.”

Other women formed a women’s group: “I think over time we had several different Marxist reading groups going on. The one I remember in Villa Road, the one I remember going to, was an all women’s Marxist reading group. Through that, I think we started to think about redefining our role as women. We were doing consciousness raising. We would go away for weekends and have weekends away and stuff. We did things like…we had a book called Our Bodies, Ourselves, which was fantastic. Women learned about how to have orgasms through Spare Rib and vibrators, which was absolutely fantastic. And, um, I think, yeah, that was brilliant. We read books, sort of Marxist books, I suppose. We did self-examination, which was quite popular in those days.

-What does that mean?

-You know, when you examine… I remember one meeting that we had a speculum, because Maureen’s a doctor. So she could have them, and we examined ourselves and learnt about our bodies. Which bit of your body? You’re getting me so embarrassed! We, you know, we tried to find out where our cervixes were, which was a journey in itself. Do you remember examining your cervix? No, I didn’t do any of that. But, yes, that was going on. Lots of use of mirrors.”

Some on Villa Road saw their inner world as the route to changing society. Luise Eichenbaum had come to London from New York as a trained psychotherapist, attracted by British feminist writing. From her squat in Villa Road, she set up the Women’s Therapy Centre with Susie Orbach, believing that therapy could be harnessed to left-wing goals. “For me, psychoanalysis and psychotherapy absolutely came right out of my political activity, because, as a feminist, we really understood that in order to change one’s self, you couldn’t just say, “I no longer want to be this person, the person I was raised to be, “the little girl raised to be a certain kind of feminine character, “who defers to people, who is submissive, who feels insecure, who doesn’t feel entitled and so on.” We knew that we no longer wanted to be that person, and so, if one wanted to change deeply, we had to look to the unconscious. I think people came to see that bringing change wasn’t just about changing physical social aspects of society. I think people started to recognise that change actually maybe has a psychological dimension, an internal dimension, as well.”

To some extent, the Villa Road community attempted to govern itself outside the scope of the law beyond:

“Would you ever have called the police?

-No.

-What did you do instead?

-Well, where there were instances of theft and so on within the street, then those were dealt with at street meetings. One incident I remember, we jailed the guy for a week, I believe. Everyone was losing their stereos and, um… we eventually managed to catch this young, black guy, who was, I think, 15 at the time. And, um, so…he said that he had been thrown out of home, that he had nowhere to go and he was stealing all this stuff so that he could survive. And so in typical Villa Road fashion, we held a street meeting, emergency street meeting, what to do about him. And we decided that we would give him a home, give him somewhere to live and we would give him money. And so he lived with us then.”

As with other squatted streets of the era, the leftist political slant of many occupants led them into taking part in solidarity action with other struggles that were going on. Villa Road residents regularly joined picket lines at strikes like Grunwick, marched in support of striking firefighters…

In response to tenants’ campaigns, the Council pressed ahead with attempts to evict through the courts, all the houses in Villa Road, which it proposed to demolish, to build a park (a part of the Brixton Plan that had survived), and a junior school (which even then looked to be in doubt). Families could apply to the Homeless Persons Unit; single people could whistle. In reply, squatters, tenants and supporters barricaded all the houses in Villa Road and proceeded to occupy the Council’s Housing Advice Centre and then the planning office.

“The barricades came about because… the, um, Lambeth Council wanted to demolish the whole of Villa Road. This had been their long-term plan. They couldn’t do it because we were living in the houses. But they, I think, probably served eviction orders on us and we decided that we were going to stay, and so, we thought, “Well, we’ll barricade ourselves in. “The bailiffs will come, but if they can’t get into the houses, they can’t evict us.” So that was another form of direct action. We would scour Lambeth, looking for wood, sheets of corrugated iron, barbed wire. There were a lot of building sites that went short of things in those days! And the ingenuity of people to get all these materials together was phenomenal. The barricade in front of 7 and 9 Villa Road was very beautiful, because we painted it. It was a carefully tended barricade. “Victory Villa” was the big sort of slogan. “Property is theft.” That was another of the slogans on the barricades. We were all into that. … The first thing I and the two chaps who moved in with me began to do was to sort out the barricades on our house. We had, um… It was like triple barricades of corrugated sheets and joists, and then more corrugated sheets, then joists and props, all put together with six-inch nails. Then on top of the barricade was barbed wire and a gutter, the plan being that we would fill the gutter with petrol and have bits of burning tyre, so we would have a sheet of flame to meet the bailiffs, before they could even get to the house itself. And we also had this huge, great, big wooden ball, like, um, on the ball and chain, but this was made of wood with big six-inch nails stuck in it, on the end of a rope, that you could swing and it would lazily move in front of the house as another disincentive to come anywhere near us.”

In June 1976, 1000 people attended a carnival organised by the squatters in Villa Road. The following day, council workers refused to continue with the wrecking of houses evicted in Villa Road, after squatters approached them and asked them to stop. Links with local workers were helped by squatters’ previous support for a construction workers picket during a strike at the Tarmac site in the town centre, and for an unemployed building workers march. They all walked off the job, and “the house became crowded with  squatters who broke out into song and aided by a violinist, started dancing in the streets.” There was a similar incident in a squat in Radnor terrace in Vauxhall, the day before. The local UCATT building workers union branch had passed a resolution blocking the gutting of liveable houses.

squatters who broke out into song and aided by a violinist, started dancing in the streets.” There was a similar incident in a squat in Radnor terrace in Vauxhall, the day before. The local UCATT building workers union branch had passed a resolution blocking the gutting of liveable houses.

In November 1976, the Villa Roaders launched an ‘Agitvan’ to tour the streets of the Borough spreading the word about life in Villa Road… These links between squatters and building workers were built on into 1977: as squatters, tenants, residents in temporary and Bed & Breakfast accommodation co-operated on pickets of the Town Hall over the Council’s housing policy. When Lambeth Council attempted to push through its demolition policy by destroying the squatted street at St Agnes Place in January 1977, Villa Roaders went off to support the occupants:

“Very early in the morning, we found out that the council were moving in bulldozers, there were large busloads of police turning up at the end of the street, and all the rest of it. We all shot off down there. Quite a lot of the residents had already climbed up onto the roofs, basically saying, “If you’re going to knock the house down, you’ll have to knock us down with them!” Got all the council workers digging up the pipes, down at the front. They filled the drains with cement, and took out water and gas pipes. They really went to town to make sure they were uninhabitable. In this picture, you can see a protester. He’s one of the squatters who tied a rope round his waist… There was a few of them. ..and actually walked across the top of this, what’s left of the main framework of the house. We, together with the lawyers from the Law Centre, managed to get an emergency High Court injunction by midday or one o’clock that day, forcing the council to withdraw their equipment, ‘and to leave us alone.’ St Agnes Place was saved, and the council was publicly and humiliatingly defeated. Lambeth Council had to rethink its approach.”

Later in the year Lambeth Housing Action Group was set up, with Tenants Associations, Squatting groups, union branches sending delegates; they pledged to co-operate with Lambeth Anti-Racist movement as well…

Villa Road was still under threat – in fact the barricades stayed up for another two years…

The following account of the battle to save Villa Road was nicked from Squatting: the Real Story, published in 1979.

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

Victory Villa Challenging the planners in South London

(Squatting: the Real Story, Chapter 12) by Nick Anning and Jill Simpson

The Planners’ Plan

The area around Villa Road is still rather quaintly labelled ‘Angell Town’ on the maps; a legacy of a past which includes the old manorial estate of Stockwell and the eccentric landowner John Angell who died in 1784.

To those who live here now, this is part of Brixton in the London Borough of Lambeth with the market and the Victoria Line tube station a few minutes walk away.

But the change wrought in just a few years by Lambeth Council’s planners has been far more radical than that gradual transformation. The majority of houses which stood in 1965 have been demolished and Villa Road too, would have disappeared if the planners had had their way. The fact that most of it still stands is the result of a protracted battle between the squatter community and the Council’s bureaucrats and councillors.

The origins of this battle can be found in The Brixton Plan, an intriguing document produced by Lambeth in 1969, and in the events that led up to its publication. Indeed, Villa Road’s very existence as a squatter community arises from the Plan, its initial shortcomings, its lack of flexibility in the face of economic changes and the refusal of leading Lambeth councillors and planners to engage in meaningful consultation. Their intransigence in refusing to admit that the plans might be wrong or open to revision was a further contributing factor.

The Plan had its roots in the optimistic climate of Harold Wilson’s first government in the early sixties. The Greater London Council (GLC) asked the recently enlarged London boroughs to draw up community plans in line with the GLC’s overall strategy for taking the metropolis gleaming into the seventies. Lambeth responded eagerly to this prompting, only too anxious to establish itself as one of the more enterprising inner London boroughs.

The scale and scope of its redevelopment plan was tremendously ambitious. Lambeth was to be transformed into an even more splendid memorial to the planners’ megalomania than neighbouring Croydon with Brixton as its showcase. Brixton town centre was to be completely rebuilt, incorporating a huge transport interchange complex where a six-lane highway, motorway box, main line railway and underground intersected.

Brixton’s social mix was to completely change with middle-class commuters flocking south of the Thames, to bring renewed prosperity and to rejuvenate business and commerce. Ravenseft, the property company which gave nearby Elephant and Castle its unloved redevelopment, expressed interest in the plan for Brixton. Tarmac, the road building firm, was given permission to build an office block on condition it helped to fund a new leisure centre. The Inner London Education Authority talked of new schools and a new site for South West London College. The dream seemed possible.

The plan would involve demolishing the fading bastions of Brixton’s Victorian and Edwardian splendour, epitomised by the very name Villa Road. These houses were to be replaced with modern homes for the working class of Lambeth. Angell Town was zoned for residential use, Brixton Road was to become a six-lane expressway and three proposed new housing developments (Brixton Town Centre, Myatts Fields and Stock-well Park Estate) would completely remove old Angell Town from the map. About 400 houses were to be demolished and their occupants ‘decanted’. Some low rise, high density modern estates were to be constructed but at the core of the plan was the construction of five 52 storey tower blocks. Brixton Towers was the apt name chosen for this development which, at 600 feet high, was to be the highest housing scheme outside Chicago. A large park was planned, in line with the GLC’s recommendations, to serve the 6,000 residents of the new estates. The scheme was a tribute to the planners’ megalomania.

The aim seems to have been to establish pools of high density council housing with limited access, restricting traffic to major perimeter roads where a facade of  rehabilitated properties would give a false respectability to a disembowelled interior. Stockwell Park Estate, the first of the three estates to be completed, has already proved the disastrous nature of this type of development. Completed in 1971, it has suffered from dampness, lack of repairs and vandalism. For several years, its purpose-built garages remained unused and, until recently, it had a reputation as a ‘sink estate’ for so-called ‘problem families’.

rehabilitated properties would give a false respectability to a disembowelled interior. Stockwell Park Estate, the first of the three estates to be completed, has already proved the disastrous nature of this type of development. Completed in 1971, it has suffered from dampness, lack of repairs and vandalism. For several years, its purpose-built garages remained unused and, until recently, it had a reputation as a ‘sink estate’ for so-called ‘problem families’.

In the heady climate of the sixties, this type of ‘macroplanning’ was taken as approved by the ballot box and by public enquiries. It was assumed that the professional planners ‘knew best’ and the majority of Lambeth’s 300,000 population were unaware of, let alone consulted about, the far-reaching nature of these plans.

First stirrings

In 1967 Lambeth Council obtained a Compulsory Purchase Order (CPO) on the Angell Town area, despite a number of objections at the public enquiry. The familiar pattern of blight set in. Residents, promised rehousing in the imminent future, no longer maintained their houses as they were soon to be demolished. Tenants in multi-occupied houses found it increasingly difficult to press the Council for repairs and maintenance, and tried to obtain immediate rehousing. The long years of Labour dominance in Lambeth were interrupted with three years of Tory rule but this was of little consequence to the monolithic plan. It drew support from Conservatives and Labour alike, although a radical caucus in the Labour Party known as the ‘Norwood Group’ began to voice misgivings during Labour’s spell in opposition. By the time Labour regained control in 1971, Angell Town was a depressed and demoralised area, as voting figures for the ward in local elections showed. Though staunchly Labour, turn-out in Angell Ward has been the lowest of all Lambeth’s 20 wards since 1971, averaging only about 25 per cent of the electorate.

The newly returned Labour administration of 1971 contained a sizeable left-wing influence through the Norwood Group and had high hopes of cutting back the massive 14,000 waiting list for council homes. However by now they were prisoners of processes originating with the Plan. Population counts in clearance areas were proving inaccurate, mainly because live-in landlords, multi-occupiers and extended families were reluctant, through fear of public health regulations, to give full details of the number of people in their houses. As ‘decanting’ took place from development areas, more and more people began to find themselves ineligible for rehousing, or were given offers of accommodation unsuitable for their needs. Most houses were boarded up or gutted, adding to blight. Homelessness grew rapidly.

Despite the Labour Group’s optimism, the building programme slowed down. Lambeth’s target of 1,000 new homes per year from 1971-8 was never met. Many people, particularly Labour Party members, began to realise that sweeping clearance programmes destroyed large numbers of houses in good condition as well as unfit ones. With a tighter economic climate and a Conservative Government opposed to municipalisation in office, some of the steam had already gone out of Lambeth’s redevelopment plans by 1971, only two years after the publication of The Brixton Plan.

The neighbourhood council

The Norwood Group of councillors both paralleled and reflected the upsurge of radical, libertarian and revolutionary politics in Brixton during the early seventies. Dissatisfaction with Lambeth’s planning processes and its inability to cope with housing and homelessness gave focus to a number of dissenting community-based groups. Activists in these groups were instrumental in establishing a strong squatting movement for single people in the main section of Lambeth’s population whose housing needs went unrecognised.

The St John’s Street Group was one of several street groups set up in 1972 under the wing of the Neighbourhood Council. Its membership included residents of both Villa Road and St John’s Crescent as the two streets were suffering from blight arising out of the same plans. Most of the immediate area was scheduled to be pulled down to form part of the new Angell Park. Villa Road tenants wanted rehousing while those in neighbouring St John’s Crescent were campaigning about the poor state of repair of their properties. The Street Group began a series of direct actions (eg a rent strike and the dumping of uncollected rubbish at the nearby area housing office) to put pressure on the Council. As a result, many Villa Road tenants were rehoused and their houses boarded up. Most also had their services cut off and drains sealed with concrete to discourage squatting. More sensibly, a few of the houses were allocated on licence to Lambeth Self-Help, a short-life housing group whose office was round the corner in Brixton Road.

Squatters enter the fray

Some of the Neighbourhood Council activists moved into No 20 Villa Road, one of the houses handed over to Lambeth Self-Help, in early 1973. That summer another house in Villa Road was squatted. No 20 became the centre of St John’s Street Group activity, providing an important point of contact with the Neighbourhood Council, Lambeth Self-Help and unofficial squatters. In 1974, other houses on Villa Road were squatted, mainly by groups of homeless single people. Many had previous experience of squatting either in Lambeth or in other London boroughs where councils were starting to clamp down on squatters, reinforcing the pool of experience, skill and political solidarity which was to be the strength of the Villa Road community. The fact that a certain number of people came from outside Lambeth was frequently used in anti-squatting propaganda.

Meanwhile, the Labour Council was moving to the right and a strong anti-squatter consensus had begun to emerge, particularly after the 1974 council elections. The new Chairperson of the Housing Committee and his Deputy were in the forefront of this opposition to squatters. Their proposals for ending the ‘squatting problem’, far from dealing with the root causes of homelessness, merely attempted to erase symptoms and met with little success. In fact, the autumn of 1974 saw the formation of All Lambeth Squatters, a militant body representing most of the borough’s squatters. It mobilised 600 people to a major public meeting at the Town Hall in December 1974 to protest at the  Council’s proposals to end ‘unofficial’ squatting in its property.

Council’s proposals to end ‘unofficial’ squatting in its property.

The rightward-leaning Council took all the teeth out of the Neighbourhood Councils and the one in Angell Ward, torn by internal disputes, ceased to function by the end of 1973. That was not to say that the issue of redevelopment for Angell Town was not still of major interest to the local residents. The Brixton Towers project had been dropped, throwing into question the whole plan. Furthermore, the programme of rehousing and demolition was proceeding slower than expected forcing the Council to consider its short-term plans for the area. It came up with the idea of a ‘temporary open space’ which was to involve the demolition of Villa Road and St John’s Crescent.

According to a Council brochure published in June 1974, this open space was to be the forerunner of a larger Angell Park with play and recreation facilities. Walkways linking the park to smaller areas of open space (‘green fingers’) alongside Brixton Road were to be built and a footbridge over that busy road was to link it with the densely populated Stockwell Park Estate.

The justification for the plan was that the high density of housing proposed for the nearby Myatts Fields South and Brixton Town Centre North estates required open space of the local park variety within a quarter of a mile radius. What was not publicly admitted was that the construction of these estates would involve a much smaller increase in the area’s population than had been originally envisaged. Instead of 3,000, the figure was now admitted to be nearer 800, hardly enough to justify the creation of a park that would involve the demolition of much good housing. In any case, money for the open space, let alone the park, was not to be available until autumn 1976, and in June 1974 housing officials declared that the Council would not require Villa Road houses until summer 1976.

Arguably, this amounted to a legal licence to occupy the houses. Probably the Council would have had little further trouble from the Villa Road squatters had it not been for two factors: the continuous programme of wrecking and vandalising houses in the vicinity and the Council leadership’s adherence to a hardline policy on squatting and homelessness. The combination of these two factors increased militant opposition to the Council’s politicians and bureaucrats which culminated in a full-scale confrontation in the summer of 1976.

A week of action in September 1974 led to more houses being squatted and saw the first meetings of the Villa Road Street Group (not to be confused with the by-then defunct St John’s Street Group). The members of the Group had come together fairly randomly and their demands were naturally different. For instance, there were Lambeth Self-Help members for whom rehousing was top priority; single people who demanded the principle of rehousing but wished to develop  creative alternatives; and students and foreigners who were in desperate need of accommodation but whose transient presence or precarious legal status kept them outside the housing struggle which was taking place around them.

creative alternatives; and students and foreigners who were in desperate need of accommodation but whose transient presence or precarious legal status kept them outside the housing struggle which was taking place around them.

By the end of 1974, 15 houses in Villa Road and one in Brixton Road (No 315) had been squatted by Street Group members who now numbered – about a hundred. Like in other squatted streets common interests drew people together and gave the street its own identity. The Street Group became a focus for the organisation of social as well as political activities. For instance, in the summer of 1975, a street carnival attracted over 1,000 people. A cafe, food co-operative, band and news-sheet (Villain) were further activities of the now-thriving street.

But it was a community living under a permanent threat and a stark reminder of that was the eviction of No 315 Brixton Road in April 1975. The house along with two others which were too badly vandalised to have been squatted, were pulled down as part of the Council’s preparation for the footbridge linking the proposed park with the Stockwell Park Estate. The dust had hardly settled after the demolition when the Council announced the cancellation of the footbridge plan. The site was left unused for five years and then grassed over.

Events like this tended to harden the opposition to the Council in the Street Group. Another five houses had been squatted during 1975, including those with serious faults which needed a lot of sustained work like re-roofing, plumbing, rewiring and unblocking drains.

The population of the street was now approaching 200. Three houses in St John’s Crescent which had been emptied in preparation for demolition were taken over with the help of the departing tenants. Several other houses in the Crescent and Brixton Road were wrecked and demolished by the Council, still intent on implementing its temporary open space plan.

Squatters were increasingly becoming a thorn in the Council’s side. Following the failure of the Council’s 1974 initiative to bring squatting under control, the Council tried again. It published a policy proposing a ‘final solution’ to the twin ‘problems’ of homelessness and squatting. It combined measures aimed at discouraging homeless people from applying to the Council for housing – like tighter definitions of who would be accepted and higher hostel fees – with a rehash of the same old anti-squatting ploys – like more gutting. The policy was eventually passed in April 1976 after considerable opposition both within the Labour Party from the Norwood Group and from homeless people and squatters.

In a sense, Villa Road, and later St Agnes Place, were the testing grounds for this new policy. Although the Council had agreed to meet Villa Road Street Group representatives in February, its position was unyielding. Twenty-one of the 32 houses in Villa Road were to be demolished within four months and the street would be closed off for open space. Moreover, the Council told the Street Group that when the houses were evicted, families would be referred to the Council’s homeless families unit but single people would just have to ‘make their own arrangements’. The future of the remaining 11 houses was less certain as they were earmarked for a junior school that, even in 1976, was unlikely ever to be built.

The Trades Council Inquiry

It was clear that the Street Group could not fight the Council without outside support. There was already considerable local dissatisfaction with the Council for its failure to change the plans for the area and the Street Group, in an attempt to harness available support, organised a public meeting in April 1976 to discuss courses of action. At the meeting, which was well-attended, it was decided to initiate a Trades Council Inquiry into local housing and recreational needs. This idea was supported by a wide range of people and groups including the vicar of St John’s Church which overlooks Villa Road and the ward Labour Party. A committee including two Street Group representatives was set up to collect evidence and prepare a report.

The Trades Council Inquiry report was to be presented to a public meeting of 200 people at St. John’s School two months later. Lambeth’s Chief Planning Officer, its Deputy Director of Housing and an alderman came to hear their critics and see the meeting vote overwhelmingly in favour of the report’s recommendations. These were:

- No more demolitions, wreckings or evictions.

- Smaller, more easily supervised playspaces should be created from existing empty sites, rather than clinging stubbornly to a plan for one large park.

- Money saved by stopping evictions, wreckings and demolition should be spent on repairs on nearby estates or rehabilitation of older property.

- The Council should recognise the strong community in the area and take that as the starting point for allowing active participation by local people in the planning process.

The Council’s representatives made no concession to these views except to suggest rather insultingly that the report might be admissible for discussion as a ‘local petition’. They firmly rejected the meeting’s recommendation that the Trades Council Report should be considered at the next Council meeting.

Whilst the Inquiry had been collecting its evidence, there had been a further series of confrontations between squatters and wreckers. The Trades Council had passed a resolution blacking the wrecking of good houses and the Council was forced to find non-union labour to do its dirty work. The squatters managed to take over one house in Brixton Road before it was wrecked (No 321) but another (No 325) was gutted by workmen under police protection. The culmination of these battles between squatters and wreckers was to be at St. Agnes Place in January 1977, an action which attracted widespread national publicity.

Both these wreckings and the Inquiry attracted local press coverage and support for the squatters widened. Several Norwood councillors, prompted by a letter from the Street Group, began to give active support as well as inside information on the Council’s position. Links with the local labour movement were helped by squatters’ support for a construction workers picket during a strike at the Tarmac site in the town centre and for an unemployed building workers march.

To the barricades

With careful timing, the Council made its initial response to the Inquiry’s report the day after it was released when all the houses occupied by the Street Group (except those on the school site) received county court summonses for possession. The court cases were scheduled for 30 June, a couple of weeks away, and the Street Group’s response was immediate: a defence committee was organised to barricade all threatened houses, coordinate a legal defence, publicise the campaign, set up an early warning system and much more.

At the court hearing, the judge criticised the Council for its sloppy preparation and only eight out of fifteen possession orders were granted. Although this was a partial victory, the barricades obviously had to remain. The Street Group embarked on a series of militant actions with support from other Lambeth squatters aimed at forcing the Council to reconsider the Trades Council Inquiry’s findings which it had rejected at a heavily-picketed meeting and at getting the Council to offer rehousing to Villa Road squatters. First, the Lambeth Housing Advice Centre was occupied for an afternoon in July and, a month later, following the breakdown of negotiations, the Planning Advice Centre received the same treatment. This did not prevent the planning and housing committees from formally rejecting the Trades Council Report but both occupations achieved their primary objective in getting Lambeth round the negotiating table. The Street Group’s initial position was for rehousing as a community but as the talks continued, it was decided to agree to consider individual rehousing. Staying in Villa Road on a permanent basis was not an option considered seriously by either side at this stage. After the second occupation and a survey of empty property in the borough by the squatters, the Council representatives said they might be prepared to look for individual properties for rehousing. The Street Group’s minimum demand was rehousing for 120 people knowing full well that any offer of rehousing would breach both the squatting and homelessness policies.

In October, the Council made an offer of 17 houses to the Street Group but the houses were in such a bad condition that the sincerity of its motives could clearly be questioned. The Street Group had no option but to reject them despite the strain that living behind barricades was causing. The defences could never be made impregnable and the difficulties of living permanently under the threat of immediate eviction was too much for many people who left, sometimes to unthreatened houses up the street. They were generally replaced by even more determined opponents of the Council and morale in the street was further boosted by the occupation of the remaining tenanted and licensed houses in the threatened part of the street whose occupants were all rehoused.

After the rejection of the offer, no further word came from the Council though it seemed clear that it was reluctant at this stage to send in the bailiffs. A war of attrition set in, marked by two interesting developments.

First, a sympathetic councillor was selected to stand in the by-election of November 1976 caused by the death of an Angell Ward councillor. The selection was a success for the Street Group’s members in the ward Labour Party whose votes were decisive. It was a rebuff for the Council’s leader whose nominee failed to win selection and helped to chip away the right’s narrow majority within the Labour Group, contributing directly to the leftward movement that eventually put the Norwood Group with a left-wing leader in power at the local elections of May 1978.

Secondly, in October, the Department of the Environment (DOE) held a public inquiry over the Council’s application to close Villa Road. Several local organisations, including the Street Group, presented evidence against closure. An inquiry which should have been over in a day stretched to ten. Each point was strongly contested since the Street Group realised that if the Council was unable to close Villa Road its plan for the park would need drastic modification. The DOE inspector promised to make his report a matter of urgency.

The turning point

As the Council still did not have possession orders on all the houses, it now restarted court proceedings against all the squatted houses (except those on the school site) – this time in the High Court. The Street  Group hurriedly drew up a detailed legal defence, arguing a general licence on the grounds that official negotiations with the Council had never been formally terminated. Villa Road’s case was strengthened by statements from two Lambeth councillors. The hearing opened in January 1977, marked by a picket, street theatre and live music outside the High Court.

Group hurriedly drew up a detailed legal defence, arguing a general licence on the grounds that official negotiations with the Council had never been formally terminated. Villa Road’s case was strengthened by statements from two Lambeth councillors. The hearing opened in January 1977, marked by a picket, street theatre and live music outside the High Court.

Judging by its legal representatives’ response at the preliminary hearing, the Council had not anticipated any legal defence and the case was adjourned twice. The Council’s reason for going to the High Court instead of the county court was that a High Court order for possession allows the police to assist directly in carrying out the eviction. A county court order did not give the police power to intervene except to guard against a possible ‘breach of the peace.’ Events at nearby St. Agnes Place in January had set an ugly precedent and showed the Council was now prepared for full scale battles with squatters. Over 250 police had arrived at dawn in St Agnes Place to preside over the demolition with a ball and chain of empty houses although the demolition was stopped within hours by a hastily initiated court injunction by the squatters.

In the event, the St Agnes Place affair put Lambeth Council at a moral disadvantage and had an important effect on events in Villa Road. Labour Group leader David Stimpson had staked his hardline reputation on an outright confrontation but the failure to demolish all the houses and the resulting bad publicity put his political future in doubt. To make matters worse for Stimpson, the DOE inspector’s report on the public inquiry into the closure of Villa Road was published around the same time. It ruled against the Council: Villa Road had to stay open until revised plans for Brixton Town Centre North were devised ‘in consultation with all interested parties’.

The remnants of The Brixton Plan had already started to crumble around the Council when Ravenseft, one of the major backers, had pulled out the previous summer. With the unfavourable report from the DOE inspector and news that the construction of the school planned for the top end of Villa Road was to be deferred indefinitely, the planners had to go back to the drawing board. The Brixton Plan was even more of a pipedream than it had been in 1969.

By the time the High Court hearing resumed in March, the Council had been forced into a position where it had to compromise. The judge encouraged the Council and the Street Group to settle out of court as, in the end, the granting of a possession order was inevitable. After some hard bargaining, the Street Group got a three months stay of execution to 3 June 1977 and costs of £50 awarded against it, a considerable saving on the estimated £7,000 the case had cost Lambeth.

June 3 passed uneventfully as did the first anniversary of the erection of the barricades. Indeed, they were to stay up almost another year until in March 1978 the squatters felt confident enough of the Council’s intentions to take them down. No attempt had ever been made to breach them.

With the DOE inspector’s decision not to close the road and the absence of revised plans for the area, the possibility now emerged that the fate of the two sides of the street could be different. The south side (12 houses) backed onto a triangle, two-thirds of which was already demolished for the open space. On the other hand, the north side (20 houses) backed onto a new council estate and its demolition would add little space to the park area even assuming that permission to close Villa Road were obtained. Therefore, the Street Group decided to accept demolition of the south side provided that everyone was rehoused, and to push for the houses on the north side to be retained and rehabilitated, ideally as a housing co-op for the existing squatters. Negotiations were resumed on this basis and Lambeth kept talking: clearly, it didn’t want a repeat of the St Agnes Place disaster.

A new Council

The first tangible gain for the Street Group came in March 1978, when two short-life houses were offered to people being rehoused from the south side. But the most important event came two months later, when a  new left-Labour Council was elected with Ted Knight, a ‘self confessed marxist’ and Matthew Warburton, a first time councillor, as leader and housing chairperson respectively. It was a significant victory in that it represented as radical a shift in policy as a victory by the Tories – in the other direction, of course. Squatters in both Villa Road and St Agnes Place had contributed directly to the leftwards swing and the new leaders had pledged to adopt more sympathetic policies.

new left-Labour Council was elected with Ted Knight, a ‘self confessed marxist’ and Matthew Warburton, a first time councillor, as leader and housing chairperson respectively. It was a significant victory in that it represented as radical a shift in policy as a victory by the Tories – in the other direction, of course. Squatters in both Villa Road and St Agnes Place had contributed directly to the leftwards swing and the new leaders had pledged to adopt more sympathetic policies.

Lambeth housing department officials now pressed for the demolition of houses on the south side, to make way for the new Angell Park, and suggested that all Villa Road Street Group members join Lambeth Self-Help Housing. It appeared that a new atmosphere of negotiation was being created but the same housing department officers did the negotiating and the Plan had not been totally abandoned. Eventually the Street Group agreed, very reluctantly, to the south side of Villa Road being vacated, with all occupants being rehoused in property with at least 18 months life. Demolition was to begin on 24 July 1978 and the fourth annual Villa Road carnival was made spectacular by one of the vacated houses on the south side being burnt down as a defiant gesture of protest. All the houses accepted for rehousing were in the borough, though some were in Norwood, several miles away.

The Street Group, left to its own devices, requested details of the Council’s plans for the rehabilitation of Villa Road north side. It’s main aim was to keep the north side houses. Inspired by the growth of housing co-ops in other areas, the Street Group decided to propose a co-op for Villa Road. In January 1979 an ‘outline proposal’ was sent to the housing directorate suggesting four possible types of co-op but with an expressed preference for a management co-op. In this type of co-op, the Council continues to own the property whilst handing over responsibilities for rent collection, maintenance and management to the co-op. Rehabilitation is financed either by local or central government. It was felt that other types of co-op involving the sale of council housing stock were politically unacceptable.

The co-op proposals were presented to the housing committee in April 1979 and formal approval was given for the chairman to continue negotiations with the Street Group for setting up a co-op. The climate had certainly changed and although squatting was still regarded as a ‘problem’, the Council now negotiated rather than evicted, at least with large groups. Lambeth officers were reluctant to embark on this scheme which was entirely new to the borough and instead suggested a joint management/ownership co-op. Houses in Villa Road would form the management wing, and the ownership branch would be in a nearby Housing Action Area. This was to ensure that four or five houses in Villa Road could be used to accommodate large families from Lambeth’s waiting list. It seemed ironic that Lambeth was now short of large houses when the previous administration had operated a policy of systematic demolition of such houses. The planning machine had done a complete U-turn.

The Street Group now had to change its tactics. Instead of militant campaigns with barricades and regular occupations of council offices, it had to get down to the nitty gritty of filling in forms to register as a friendly society and as a co-op, finding a development agent (Solon Housing Association was eventually selected) and working out detailed costings for the rehabilitation. It was no longer a matter

of just saving the houses, it was a question of getting the long-term best deal for Street Group members and Lambeth’s homeless.

After Solon had submitted detailed costings in January 1980 (it worked out at about £7,000 per bed space), the housing committee agreed, the following month, to support Villa Road’s application to the Housing Corporation (a quango through which government money is channelled to housing associations and co-ops) for funding to rehabilitate the houses. Lambeth would grant Villa Road a 40 year lease. The recommendations were not passed without dissent. Some of the old anti-squatting brigade were still on the committee, intent on eviction without rehousing for Villa Road squatters. But Street Group members now no longer had to live day to day under threat of eviction – they could dream of still living in Villa Road and collecting their pensions.

Not everything was different. Two houses on the corner of Villa Road, Nos 64 and 66 Wiltshire Road were demolished in April 1980. They had been squatted in October 1976 following an unsuccessful wrecking attempt by the Council. They had provided housing for some 20 people for three and a half years and were now being pulled down to make way for the Angell Park play centre scheduled to start in June 1980. Yet three months later, not a brick had been laid. At least now Lambeth offered all the occupants short-life or permanent rehousing.

The first scheme was rejected by the Housing Corporation but a different plan was submitted in July 1980 involving the conversion of the houses to accommodate 12 or 13 people each, rather more than the number already living there. Conversion costs were appreciably lower (under £4,500 per bed space) and the scheme had, in the words of the manager of the housing advice centre, ‘top priority’ from the Council with support from both council officers and councillors.

Victory Villa?

The change in relationship between Villa Road, a squatted street in Lambeth, and the local council between 1974 and 1980 from a harsh anti-squatting policy to negotiations for a housing co-op could not have been more dramatic. But what else has been achieved by six years of squatting in Villa Road? The squatters arrived late in Angell Town and it would be nice to imagine that had they arrived earlier, they would have posed an even greater challenge to the lunacies of the planners. But, in the event the achievements of the squatters have been significant, both for themselves and for the immediate community:

- Homes have been provided for the equivalent of 1,000 people for a year in houses which would otherwise have been gutted or demolished.

- About 25 people have obtained two year licences and 15 have obtained council tenancies from Lambeth.

- About 160 people are in the process of obtaining permanent housing as a co-op, remaining together as a community. Working with Solon’s architects, they will be able to have a considerable measure of control over the rehabilitation of the houses, retaining many of the collective arrangements and physical adaptations which have developed over the years.

• Twenty elegant 19th century houses have been saved from demolition and a useful street prevented from being closed. - Control of Lambeth Council has significantly shifted partly thanks to the Villa Road squatters.

And, less tangibly, although few people stayed in Villa Road for all the six years of struggle, a cohesive street community was created which many people enjoyed living in. Squatters in Villa Road, like those in other streets in Lambeth which won concessions from the Council (St Agnes Place, Heath Road, Rectory Gardens, and St Alphonsus Road) challenged the complacency and smugness of the bureaucrats and won. That was the real victory in Villa Road.

What happened in Villa Road could have happened just as easily in other blighted streets in Lambeth or elsewhere. The squatters organisation, their use of direct action and their insistence that planning and housing are two sides of the same coin challenged the complacency and smugness of the bureaucrats. Villa Road’s real victory was to prove that plans are not inviolable, and that people can affect and be directly involved in planning processes that determine their living conditions. Considering what Villa Road was up against, that is no small achievement.

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

Some of those moved from the demolished ‘south side’ houses in Villa Road were rehoused in council-owned shortlife property – including the flats in mansion blocks on Rushcroft Road, next to the Library in central Brixton. They would face 20 years of mismanagement, bad repair, and uncertainty from Lambeth Council and then and London & Quadrant Housing Association (after the flats were off-loaded onto L&Q)… and then eviction in the early 2000s as the Council decided to flog off their flats off to developers. However, many of the flats cleared of short-lifers were then squatted again – a mass eviction of 75 squatters took place as late as 2013.

The houses on the north side of Villa Road mostly remained, becoming a housing co-op which survives – although many of the original residents moved out gradually, lots of other ex-squatters, subversives and other ne-er-do-wells have passed through since then…

In 2006, the BBC screened one episode of a series called Lefties which interviewed ex-Villa Road residents, you can watch it on youtube:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Erp2utEgZp4

Some of the above info was gleaned from the transcripts from this program.

Read a slightly longer account of the growth of squatting in Brixton, with more details on the Brixton Plan.

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

past tense’s series of articles on

Brixton; before, during and after the riots of 1981:

Part 1: Changing, Always Changing: Brixton’s Early Days

2: In the Shadow of the SPG: Racism, Policing and Resistance in 1970s Brixton

3: The Brixton Black Women’s Group

4: Brixton’s first Squatters 1969

5: Squatting in Brixton: The Brixton Plan and the 1970s

6. Squatted streets in Brixton: Villa Road

7: Squatting in Brixton: The South London Gay Centre

8: We Want to Riot, Not to Work: The April 1981 Uprising

9: After the April Uprising: From Offence to Defence to…

10: More Brixton Riots, July 1981

11: You Can’t Fool the Youths: Paul Gilroy’s on the causes of the ’81 riots

12: The Impossible Class: An anarchist analysis of the causes of the riots

13: Impossible Classlessness: A response to ‘The Impossible Class’

14: Frontline: Evictions and resistance in Brixton, 1982

15: Squatting in Brixton: the eviction of Effra Parade

16: Brixton Through a Riot Shield: the 1985 Brixton Riot

17: Local Poll tax rioting in Brixton, March 1990

18: The October 1990 Poll Tax ‘riot’ outside Brixton Prison

19: The 121 Centre: A squatted centre 1973-1999

20: This is the Real Brixton Challenge: Brixton 1980s-present

21: Reclaim the Streets: Brixton Street Party 1998

22: A Nazi Nail Bomb in Brixton, 1999

23: Brixton police still killing people: The death of Ricky Bishop

24: Brixton, Riots, Memory and Distance 2006/2021

25: Gentrification in Brixton 2015

2 responses to “Spotlight on London’s squatted streets: Villa Road, Brixton”

[…] most squatted borough in London. The upsurge created whole squatted communities and experiments: Villa Road, the Railton Road/Mayall Road in Central Brixton (known as the frontline); St Agnes Place and Oval […]

LikeLike

[…] in 1977 towards the end of the big wave of squatting in the ’70s. After the battle of Villa Road, Lambeth Council had toned down its anti-squat policies and many squats became housing Co-ops and […]

LikeLike