When World War 1 came to an end, in November 1918, there were millions of men in uniform across Europe. After the initial nationalist fervour and pro-war enthusiasm that had seen mass enlistment in the first year or two, the war fever had largely abated. Mass slaughter, the stalemate of trench warfare, the horrors of soldiers’ experience – trauma, disease, cold, horrific wounds, as well as vicious military discipline, punishment of those who refused orders, were unable to fight any more… Many of those on the many fronts across the continent had been conscripted.

After over 17 million deaths and even more wounded, all most of those in the respective armies wanted to do was go home. Long years of war had left widespread cynicism and disillusion with the war aims, with the high command, with pro-war propaganda…

Out of this war-weariness, and inspired by the Russian Revolution of 1917, (itself a product of army mutinies and revolts from a population enraged by the privation and poverty the war had aggravated), French and British army mutinies had erupted in 1917-18. Revolts, mutinies and uprisings among her allies left Germany mostly fighting alone by the beginning of November, and German mutinies had played a major part in Germany’s decision to open talks about ending the war with the allies…

But celebrations of peace were somewhat premature. Several western governments, notably Britain, France and the US, were determined not to end the fighting, but to carry on the war – against their former ally, Russia.

After the October Revolution had overthrown the liberal government there, the new Bolshevik government had fulfilled one of the main aims of the revolution – to pull Russia out of the war.

This in itself enraged France and Britain, as it left Germany free to move large forces to the western front. But the overthrow of tsarism and then the bourgeois Kerensky government, and the beginnings of social revolution across Russia, also terrified governments worldwide. And the leading allied nations were among the most worried. What if workers across Britain took Russia as an example? There had already been a huge upsurge in workplace organising, strikes, and social struggles as the war progressed… The British and French establishments were determined not only that radicals inspired by the Soviet upsurge be repressed, but to organise military intervention in Russia, to support the anti-revolutionary forces already fighting a civil war there, and if possible help them restore a more acceptable regime and crush working class power.

By this time of course, in Russia itself, the processes were already at work that would hamstring working class control and produce a Bolshevik dictatorship which would largely destroy any real communist potential within 3 years… However, it was all one to the western powers.

Plans to mobilise some of the millions conveniently still under orders and turn them against Russia were already underway long before the Armistice between Germany and the Allied powers was signed on 11 November.

An agreement had been drawn up in December 1917 between France, Italy and Britain to act against the Bolshevik regime, subsidise its opponents, and prepare ‘as quietly as possible’ for war on them.

Between February and November, British troops had already been sent to invade parts of Russia. Clauses within the peace agreement itself make it clear that troops were to be moved across Europe to the east, and ensured that free access to the Baltic and Black Sea for French and British navies would ease plans to invade Russian territory.

And immediately after the ‘peace’, plans were stepped up, along with a concerted propaganda campaign against ‘bolshevism’ in the press, designed to whip up support for military intervention.

But the plans involved reckoning on thousands of soldiers as pawns, and that British workers would have no view or no say in the matter. This was to be a serious miscalculation.

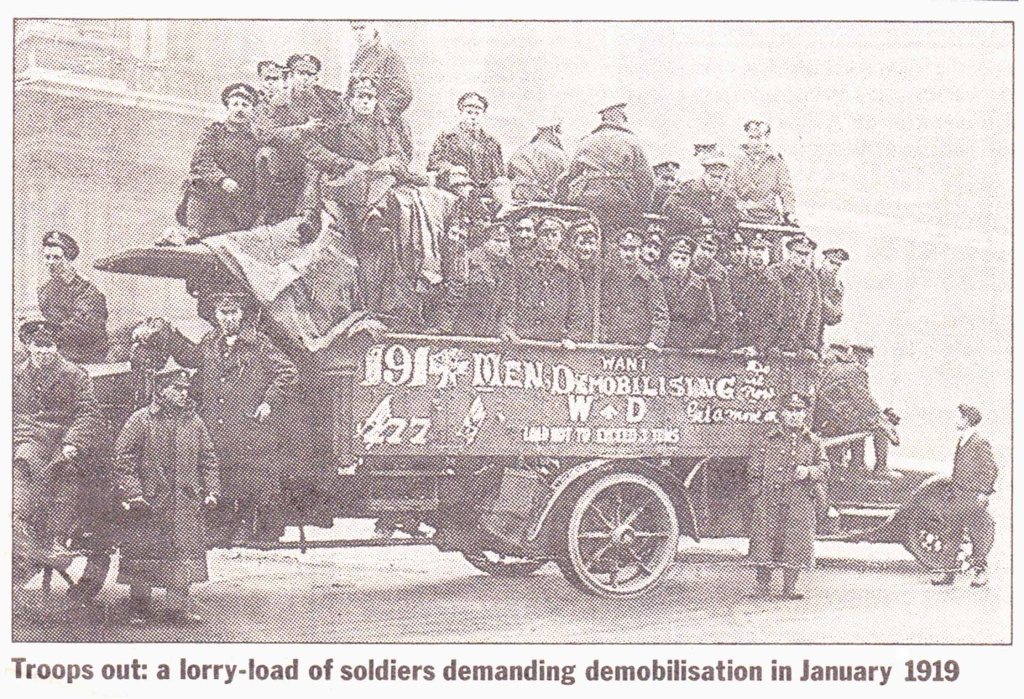

In the early months of 1919, there were still over a million British soldiers still in uniform, some in France but many more in army camps in this country. Many were expecting immediate demobilisation now the war was over; this expectation turned to frustration and then to eruptions of protest. Attempts to delay demobilisation in order to facilitate intervention in Russia were certainly going on, but bureaucratic delays and simple problems of scale were also for sure causing backlogs and a slow process of sending soldier home. But in January 1919, a number of mutinies, protests and demonstrations in army camps in southern England and around London, demanding immediate demobilisation, broke out, causing serious alarm in government circles; especially as industrial unrest was increasing. Mutinies, links between discontent in the armed forces and on the home front had led to the Russian Revolution and to revolutionary uprisings still then raging in Germany, Hungary and elsewhere…

Preventing millions of enlisted and conscripted soldiers from returning to civilian life when the war was over was bound to spark resentment – the only question was how this would be expressed, as grumbling, or active protest.

The answer soon came, appearing first of all in army camps in Folkestone and Dover, on the south coast of England.

“On the morning of Friday, 3 January 1919, notices were posted that 1000 men were to parade for embarkation at 8.15 a.m. and another 1000 were to parade for embarkation at 8.25 a.m. The men wrote across them: ‘No men to parade’. Word was passed along from rest camp to rest camp that men in one, nearly 3000 of them, had held a meeting and had decided not to march down to the boat, but to visit the mayor of Folkestone. Shortly after 9 a.m. a large body of men from No. 1 Rest Camp marched in orderly fashion to No. 3 Rest Camp at the other end of the town. There the column was heavily reinforced, and all marched down the Sandgate Road to the Town Hall. On the way they shouted in chorus: ‘Are we going to France?’ and answered with a louder ‘No!’ Then: ‘Are we going home?’ – and in response a resounding “Yes!’ Over 10,000 men assembled at the Town Hall. Several climbed on to its portico and delivered speeches: their complaints that many applications for demobilisation, in order to return to waiting jobs, were being ignored, were greeted with cheers. The mayor told the men that if they went back to camp they would hear good news: a remark answered by the singing of ‘Tell Me the Old, Old Story’! During the demonstration at the Town Hall the soldiers saw an officer taking photographs from the window. They entered the building and demanded an interview with him. He turned out to be an Australian taking the pictures as a souvenir, and offered the film to the soldiers – which they accepted. Finally, the town commandant, Lieutenant-Colonel H.E.J. Mill, promised the men that if ‘any complaints would be listened to’: and they then returned to their camps in a long procession, preceded by a big drum. At the camps they were told (1) that the pivotal and slip men who had work to go to could, if they wished be demobilised at once, from Folkestone; (2) that those who had any complaints could have seven days’ leave in order to pursue their case; and (3) that those who wished to return to France could do so. ‘They seemed reassured,’ reported the Times Correspondent, who underlined that there had been ‘no rowdyism’. He said that later a number of the men did return to France: however, the Daily News correspondent wrote that the morning mail boat to France had sailed without any troops.

On Saturday morning, 4 January, there was a new demonstration. Despite the assurances given the previous day, ‘a certain number’ had been ordered to France that morning. They refused, and a large number marched to the harbor to station pickets there, while other pickets were posted at the station, meeting the trains with men returning from leave: all joined the strike. Only officers and overseas troops embarked on the boats for Boulogne, which left ‘practically empty’. According to the Morning Post correspondent, an armed guard had been mounted at the harbour,

‘whereupon a representative of the soldiers threatened that, if it remained, they would procure their arms from their quarters at the rest camp and forcibly remove the guard. The latter was consequently withdrawn, and the malcontents placed pickets at the approaches to the harbour to prevent British soldiers from entering. Dominion soldiers were allowed to go.’

Probably about the same incident, a Herald investigator several days later said that the guard consisted of Fusiliers with fixed bayonets and ball cartridges. When the pickets approached, one rifle went up: ‘the foremost picket seized it, and forthwith the rest of the picket fell back’. Everywhere the feeling was the same, he said: ‘The war is over, we won’t fight in Russia, we mean to go home’.

The same reporter stated that the soldiers also tore down a large label, ‘For Officers Only’, above the door of a comfortable waiting room. The Times report went on to say that several thousand men, including the new arrivals carrying their kits and rifles, marched to the Town Hall, where they were once again addressed by their spokesmen. It was announced that a ‘Soldiers Union’ had been formed, and that it had elected a committee of nine to confer with the authorities in the Town Hall. There would be, immediately afterwards, a meeting with the general and town hall commandant at No. 3 Rest Camp. The whole mass of about 10,000 men marched there to await the report of the conference, which lasted into the afternoon. Finally, the delegation announced to the soldiers that the pledges made the previous day had been renewed. Late that evening, in fact, special staff from the Ministry of Labour arrived, and went to each rest camp to complete the necessary formalities.

One more the correspondent remarked that there had been ‘no rowdiness’, and that the townspeople spoke ‘in the highest possible terms’ of the soldiers’ behaviour. Thereafter everything proceeded as had been agreed.

It is not without interest that, as it turned out, one of the nine delegates was a solicitor in civil life, and another a magistrate. The composition of the delegation was: one sergeant of the Army Service Corps (chairman), a corporal of the Royal Engineers, a gunner of the Royal garrison Artillery, and the rest privates, several of whom were trade unionists.

After this unprecedented action at Folkestone, another took place at Dover on Saturday 4 January. About 2000 men took part, holding a meeting near the Harbour Station, at which a deputation was elected to see the military and civil authorities. The Daily Chronicle report gave further details:

‘A number of men had reached the Admiralty Pier , where transports were waiting for them, when suddenly there was a movement back, and men began to leave the pier. They streamed off along the railway, in spite of official protests, and on their way to the town met a train loaded with returning troops bound for the pier. The soldiers called on the newcomers to join them, and the carriages were soon emptied. Continuing their march, and all in full field kit and carrying their rifles, the troops mustered at Creswell, and from the railway bridge some of their number addressed the others on demobilisation grievances. They decided to send a deputation to the military and civil authorities, and the men then fell in and marched to the Town Hall, which was reached just before 10 o’ clock… The troops represented scores of different units, and a number of Canadian and Australian men.’

At the Town Hall, they formed up on either side of the road and in the side streets. The mayor admitted them into the Town Hall, and the overflow into the adjoining Connaught Hall. While waiting for a reply from the military authorities, the men sang popular songs, and the arranged for their free admission to the cinema. In the afternoon, at the Town Hall, they received promises that grievances would be ‘looked into’, and returned to their rest camps. A War Office statement printed by the Times said that the soldiers’ representatives were seen first by General Dallas, GOC Canterbury, and then by General Woolcombe, head of the Eastern Command. He had returned from leave when hearing of the ‘trouble’, and from Folkestone had telephoned he Home Army Command at the War Office for instructions. A report in the Times next day stated that ‘all cases had been enquired into’, and that soldiers were being allowed freely to telegraph their employers: if the latter replied favourably, the men could go home to start work at once.

Later on Friday, 3 January, the London evening papers had printed brief accounts of what was happening at Folkestone: which of course had become known at Dover. But almost immediately, in the words of the Evening News the following Monday, ‘the censorship came into action, with the result that all authentic news was stopped’ (though the Star, on Saturday, 4 January defied the ban). There can be no doubt about the military authorities’ reaction. The London letter in the Plymouth Western Morning News on 6 January, referred to ‘someone’s desire to conceal the truth: an attempt had been made on Friday and Saturday to hide the trouble at Folkestone… despite the efforts of the War Office to conceal it, nearly 10,000 men took extreme action’. The Birmingham Gazette on 8 January confirmed that ‘when the Folkestone trouble first arose, the War Office invoked what is left of the censorship system to keep the whole matter out of the newspapers.’ And on the same day The Ties, evidently more directly accessible to War Office pressure than the provincial press, revealed another aspect of the events by now occurring in many places when it stated in its leading article:

We are asked to publish, but have no intention of publishing, a great many letters on the subject of demobilisation which show the deplorable lack of responsibility on the part of the writers… fanning an agitation which is already mischievous and may become dangerous… These demonstrations by soldiers have gone far enough.

But The Times was too late. The demonstrations had certainly spread far beyond Folkestone, thanks to the reports in Friday’s evening papers: The Times itself had to report, on Tuesday 7 January, that the Folkestone and Dover demonstrations had been ‘followed by similar protests in other parts of the country’, and there might be more that day.

At other camps in Kent the demonstrations had already begun. At Shortlands, near Bromley, where there was a depot of 1500 men of the Army Service Corps, a committee of twenty-eight had been formed at breakfast on 6 January, including five NCOs [non-Commissioned Officers – officers who had risen through the ranks from private. Ed] and three cadets. Their chairman was a private from Canada, who had been at the front, and been transferred to the ASC. They marched in column to Bromley, where they held a meeting in the Central Hall. The chairman stated their main grievances: delay in demobilisation, and being held in the army to do civilian work. During the meeting a message arrived at the camp, saying that there would be no more drafts overseas, those men already out on a convoy would be sent back to the depot, and demobilization would start on Wednesday, 8 January. On their return, the commanding officer asked for names of the ‘ringleaders’, but this was refused, and next morning he had a two-hour meeting with the committee. Apart from the promises already made, he agreed to send to the War Office a ‘points system’ of priorities for demobilisation which the committee had drawn up. This provided: married men with work to go, and those running a one-man business – 1 point; years of service to be additionally credited a follows: 1914 4 points, 1915 3 points, 1916 2 points, 1917 1 point; men over military age, 1 additional point; those transferred from the infantry, 1 additional point. It appointed a sub-committee of five to visit other ASC Depots in the London area… On 8 January the committee issued a statement that all the other ASC depots had approved the scheme, but with 2 points instead of 1 for men with one-man businesses. Two days later demobilisation began.

At Maidstone on 7 January, a demonstration of several hundred soldiers of the Queens, 3rd Gloucestershire and 3rd Wiltshire Regiments, marched down the High Street at 10 a.m., and held a meeting explaining their grievances. Thence they marched to the Town Hall, where the mayor received a deputation from them and promised to forward their representations to the proper quarters. The demonstration had been preceded by interviews with their officers, at which the soldiers had demanded an end to unnecessary guard duties, drill and fatigues. During the afternoon demonstrations it became known that these demands had been conceded. The demonstrations had been renewed by 600-700 men of all three regiments.

At Biggin Hill, Westerham, on 7 January, some 700 men working on aeroplanes and wireless instruments refused to go on parade, and took possession of the camp. All its sections were placed under guard except for the officers’ quarters. They got ready twenty-eight motor wagons for a journey to Whitehall. They were persuaded not to see the plan through by the ‘tactful speech’ of their former colonel, who addressed them in a large hangar. The next day (8 January) he promised his help if they put their grievances in writing. This they did, complaining of: (1) insufficient food, badly cooked; (2) indescribable sanitary conditions, with eight washbasins for 700 men; (3) exploitation by officers, who required the men to do private jobs for them; and (4) delays in demobilisation. The ex-colonel offered to accompany a deputation to the War Office if required. On 9 January officials from the War Office visited the camp, and made immediate improvements in the sanitary and working conditions. On 10 January all except thirty-four men were sent home on ten days’ leave. Meanwhile, on 8 January, a number of RAF lorry drivers had refused to convey the 200 civilians working on the aerodrome from their homes in South-East London several miles away; this had been done previously by civilian drivers, and the RAF men demanded pay for this work at civilian rates. They resumed work on 11 January, after an investigation had been promised.

At Richborough ‘there was a demonstration by troops’ on 8 January’; but beyond this bare mention in Lloyd George’s own paper, nothing so far had been found.

As the London newspapers were already reporting the early strikes at Folkestone and Dover, unsurprisingly, the movement soon spread to the capital and its environs:

“At Osterley Park – a big manor house in its own grounds, west of London – at least 3000 men of the Army Service Corps were stationed. Most of them had served in France, and had been wounded, in the infantry; later they had been drafted into the ASC, and nearly all were ex-drivers of London buses, many with long trade union experience. They had recently laid their grievances about demobilisation before their commanding officer, but had had no definite reply. Accordingly, on Monday, 6 January, the soldiers broke camp, and about 150 took out three lorries and drove to Whitehall, intending to call on Lloyd George. They told reporters that more would have come with them, but officers had removed parts of the mechanism of other lorries. From Downing Street, where they were joined by man of other regiments, they went to the Demobilisation Department at Richmond Terrace, where a deputation of six was received by a staff officer of the Quarter-master-General’s department. He informed them that from Wednesday 8 January, 200 a day would be demobilised, adding that their complaints could not be investigated unless they returned to camp. This they did, followed by several staff officers and Ministry of Labour officials in a car. In the afternoon a second deputation of two privates came to Whitehall from a meeting of both ASC and other units. The War Office later issued a statement to the meeting saying that a beginning had already been made with dispersals for the Army Ordinance Corps, the Army Service Corps, the Army pay Corps and other military organisations. Meanwhile, at the afternoon parade in Osterley, a staff major had also told the soldiers that the Army Council, in session on Saturday 4 January, had decided to put the Army Service Corps on the same footing as other units, and that none of them would be sent on draft overseas.

The special significance of the latter assurance is underlined by a statement in the evening Pall Mall Gazette, on the day of the demonstration, that ‘the excitement among the Army Service Corps at Osterley and elsewhere is attributed in many quarters to oft-repeated rumours that plans are being prepared for the sending of a force to Russia’. In spite of assurances received on this score, all training ceased on 7 January, and 100 men were told they were being demobilised immediately. The demonstration of the others proceeded the following day.

At Grove Park (southeast of London), about 250 Army Service Corps drivers broke camp on 6 January and marched to the barracks half a mile away, asking to see the commanding officer. A sergeant-major who tried to stop them at the gates was knocked over in a scuffle, and the men entered. There they were ‘met in a conciliatory spirit’ by a senior officer, who, standing on a box, expressed sympathy with their grievances, and said everything in the officers’ power was being don to secure their release. A spokesman of the men said that many of them had had letters from their employers offering them re-employment, but nothing had been done, and they were being kept in the army doing no useful work. At the commanding officer’s request, they paraded again after dinner and filled in ‘Form Z16’ (for demobilisation). Fifty men who had been ordered to go to Slough, three hours journey by lorry to scrub huts, refused, saying it was unreasonable to expect men to stand closely packed in lorries for such a period.

At Uxbridge (North-West London), on Monday 6 January, 400 men from the Armament School (used as a demolition centre) broke camp at midday and marched along the High Street singing ‘Britons Never Shall be Slaves’ and ‘Tell Me the Old, Old Story’. At the market place they held a meeting, where they were addressed by the commandant, and then marched back. One of them told a reporter that, apart from the slowness of the demobilisation, ‘the food had been rotten since the Armistice, 1 loaf between 8 men, 5 days a week sausage.’ That morning the men had upset the tables, and gone out. On their return they formed a Messing Committee composed of 4 or 5 privates, 1 sergeant and 1 officer. Not satisfied, on Tuesday 7 January, they set up a Grievance Committee in each squad, composed of officers as well as men, to bring forward their complaints to the commandant. They also sent a deputation by lorry to the War Office.

From Kempton Park (southwest of London), on Tuesday 7 January, shortly before 3 p.m., thirteen large army lorries drove to the War Office in London, with forty to fifty soldiers in each lorry. General Burns had visited the depot that morning, but had not been able to give them any satisfaction. All were in high spirits, ‘determined to get what they called their rights. On the lorries they had chalked ‘No red tape’, ‘We want fair play’, ‘We’re fed up’, ‘No more sausage and rabbits’, ‘Kempton is on strike’. Held up at the Horse Guards (the War Office), they elected a deputation of eleven, which went into he War Office ‘amid ringing cheers’. The result of the interview was not published, but it could not have differed from what was secured elsewhere.

At Fairlop naval aerodrome (near Ilford, east of London), orders were posted on the morning of 7 January that eighty men were to proceed to other camps. All 400 men paraded and asked for a conference with the commanding officer, Colonel Ward: the transport men meanwhile got out their lorries to go to Whitehall, should the interview prove unsatisfactory. The colonel, however, came to a mass meeting held in a hangar, and agreed that every man with papers showing he had employment to go to, or who came from a one-man business, should have a day’s leave immediately, to get the papers endorsed, and could then go home pending demobilisation.

At the White City (well within the boundaries of West London itself), about 100 Army Ordnance Corps men on 7 January refused to leave barracks for the 1.30 p.m. parade, and sent a deputation to one of the officers demanding (1) speedier demobilisation, (2) shorter working hours, (3) no church parades on Sunday, and (4) weekend passes when not on duty. They asked for a definite answer within a week, and meanwhile resumed duty.

In the Upper Norwood Camp (in South-East London), there was a distribution centre for men discharged after lengthy illness. ‘After many previous discussions among themselves’, they sent a deputation on Sunday, 5 January, to interview the commandant. Then, on 6 January, they discussed with him complaints raised by the men, chiefly, that, even after twenty-eight days in hospital, they were being discharged.

But the most impressive demonstration of all in the London region, was that at Park Royal (in North-West London) on 7 January, where there were 4000 men of the Army Service Corps. That day a committee elected by the soldiers submitted to their commanding officer the following demands: (1) speedier demobilisation; (2) reveille to be sounded at 6.30 in the morning, not 5.30; (3) work to finish at 4.30 in the afternoon, not 5.30; (4) no men over forty-one to be sent overseas; (5) all training to stop; (6) a large reduction of guard and picket duty; (7) no compulsory church parade; (8) no drafts for Russia; (9) a committee of one NCO and two privates to control messing arrangements for each company; (10) a written guarantee of no victimisation. Most of these demands were agreed to.

However, at 1 p.m. on 8 January a big deputation arrived at Whitehall to present heir demands themselves. This had been agreed to by the committee: they left volunteers behind to look after the 300 horse at the depot. Their intention was to see the Prime Minister.

At Paddington, and again at the Horse Guards parade ground, they were met by General Fielding, commanding the London district, who tried to stop them, even threatening to use the police against them. Fielding promised them that demobilisation would take place ‘as soon as possible’: but as regards the assurance which they wanted that ‘they would not be sent to Russia’, he could give them none. This failed to satisfy them; they defied him, and marched in a body to Downing Street. Apparently the general told them ‘they were soldiers, and would have to obey orders’.

Finally Sir William Robertson, former Chief of the Imperial General Staff, came out to speak to them and hear their demands. He agreed that the commanding officer of the Home Forces should receive a deputation of one corporal, one lance-corporal and one private for half an hour. The deputation returned with a group of officers, who announced that the outcome of the talk was satisfactory, and Sir William Robertson had promised to send a general to Park Royal to investigate their complaints. While all this was going on, crowds of the general public were watching the proceedings and encouraging the men. One of the offices invited the men to go back to camp. But they insisted that first of all they must hear a report from the deputation itself. Two or three of its members spoke. They confirmed that the same percentage of men at Park Royal would be demobilised as elsewhere: no one who had been overseas or was over forty-one would be sent on draft – ‘including to Russia’, added the Daily Telegraph reporter – and those already notified for draft were to be sent on Christmas leave, if they had not been already.

On their return, the men held a meeting in the canteen and expressed their satisfaction at the settlement.

Among the demonstrators at the War Office on 6 January were 259 soldiers due to return from leave to Salonika. They were nearly all time-expired men who had served in Greece (some for as long as three years) and before that in India. They were addressed by the Assistant Secretary for Demobilisation, General de Saumarez, who told them that those with demobilisation papers already prepared would be discharged immediately, and the remainder could go to the reserve battalions at home. If they could get their employers to send them the necessary form requesting their discharge, they too would be demobilised at once. Next morning, Thursday 9 January, after assembling at the War Office again, they were marched to Chelsea Barracks, and there either demobilised or sent on fourteen days leave for the purposes indicated.”

The events continued to spread around the country and among British soldiers stationed in abroad, including those already embarked for intervention in Russia. We don’t have space to detail all of it here, but there were protests, strikes and subsequent negotiations – at Lewes, Shoreham, Smithwick;

at Aldershot, Winchester, East Liss, Beaulieu Camp near Lymington, on the Isle of Wight… Bristol, Falmouth, on Salisbury Plain, Newport and Swansea… Felixstowe, Bedford, Kettering, Harlaxton in Lincolnshire; at Leeds, Manchester, Blackpool; in Scotland – at Edinburgh, Stirling, Leith, Rosyth and Cromarty…

In Southampton, in ‘mid-January… the docks were in the hands of mutinous soldiers and 20,000 men were refusing to obey orders… deserted troop ships picketed by soldiers’. Lord Trenchard, sent to sort the situation out, was shouted down and hustled when he went to speak to 5000 men in the customs sheds. He ordered 250 soldiers from the nearby Portsmouth garrison marched to the sheds and load their rifles, he forced the men’s surrender, and used water hoses to drench and subdue 100 others… More than some of the other protest, the Southampton situation scared the government, who saw it as an embryonic soviet, and repressed any mention of it in official papers or memoirs for decades.

The spirit of rebellion spread, if much more uncertainly, to the navy: at Milford Haven, where there was a ‘mutiny not accompanied by violence, on board a patrol ship, the HMS Kilbride: the men refused to carry out their duties on the pay they were receiving (in contrast to the way the army dealt with the protests, 7 sailors were court-martialled for this, 1 being sentenced to 2 years hard labour, 3 to 1 year and 3 to 90 days detention);

at Devonport, where the lower ranks elected a committee to air their demands;

at Liverpool…

The protests, rebellions and mutinies were not limited to Britain – because the majority of British soldiers were still posted overseas. British soldiers in France erupted in much the same way as the British-based squaddies had done. There was unrest and some rioting, across many detachments. The climax was an outright mutiny at Calais, on 27 January. After a private was arrested for making a seditious speech, railwaymen and Army Ordnance Corps men went on strike; although the private was quickly released, this sparked a strike among 5000 soldiers, who demanded immediate return to England, with leave to seek employment. The soldiers’ mutiny was heavily repressed with armed force, and the ‘ringleaders’ received long sentences at court-martial; the Army Ordnance Corps protest lasted longer, and won some concessions. But discontent went on, and there was some fighting after one of the most vocal was nicked.

Read a first-hand account of the Calais Mutiny

There were also similar rebellions at Le Havre, Etaples (scene a year and a half before of a serious wartime mutiny), Boulogne, and Dunkirk.

… and among troops already involved in the British-allied plan to intervene militarily in Archangelsk, in northern Russia to support ‘white’ (anti-Soviet) forces. British, French, American and Polish forces were under British command here, but socialist propaganda and discontent were rife, and news of the demob protests reached these troops via socialist papers. Troops in Archangelsk refused orders to advance, mass meetings were held, and committees elected, and the commanders of the invasion force reported back to London that they were not confident of the men’s reliability. Some ‘ringleaders’ had to be arrested… But a serious blow was dealt to the allied attempt to smash the Russian Revolution by force.

The soldiers’ strikes not only forced the government to speed up demobilisation and lightened wartime conditions for those awaiting release.

It also did make the government think twice about conscripting soldiers into an intervention force for sending to Russia. Clearly squaddies were not necessarily going to be happy to be pawns this time. Public opinion in Britain was already heavily against intervention in Russia… But the widespread and almost immediate concessions to the protests show the scale of the terror that the British government was barely managing to conceal – that the increasing industrial unrest, social weariness with war privations and dissent among the forces would link up, as they had in Russia… The idea of a British Revolution may seem ridiculous now, but it seemed a genuine possibility in 1919… If you lose control of the armed forces (not forgetting that the police also went on strike I 1918 and 1919…)

The soldiers strikes of January certainly scotched the idea that a mass military force could be sent to help smash the Russian Revolution. It wasn’t the end of the British government’s plans to support the ‘white’ armies fighting against the Bolsheviks: attempts to send arms and other aid to the white Russian forces continued for over a year and a half, but were eventually in practical terms scuppered by the organised action of workers on the docks.

In fact though the fear of the British authorities that the soldiers’ strikes could develop into revolution was very likely overstated. Overwhelmingly the demonstrations, even when they became more confrontational, was for immediate demands, and largely subsided when they were granted. As a leading historian of WW1 mutinies and dissent concludes:

“most of these affairs focussed on the men’s demand for immediate demobilisation. With few exceptions, notably the confrontations at Folkestone, Dover and Whitehall, the demobilisation mutinies were dealt with by local and regional Commands. Their cumulative effect was serious because it caused the Government to accelerate demobilisation. But even the most optimistic socialists never felt it was a prelude to revolution. For example, the British Socialist Party newspaper, The Call, on 16 January 1919, commented: ‘The soldiers’ strike has arisen primarily out of disgust with which the intelligent fighting man regards the attempt to deal with him on the question of demobilisation as with an unreasoning machine and that it is not the outcome of considered revolutionary opinions, it would be foolish to dispute.’

Though the Communist historian Andrew Rothstein has tried to politically inflate these events into a tribute to the Russian Revolution, where a mutinous flag was flaunted it was the Cross of St. George or the Union Jack, rather than a rebellious red banner. Furthermore, few politically significant links were sustained between the mutineers and their turbulent industrial counterparts.” (Julian Putkowski, A2 and the Reds In Khaki)

Interestingly, though, the text from which this quote was taken details the extent of British secret state spying on soldiers’ and ex-servicemens’ organisations that sprang up in 1919, most notably the Sailors’ and Soldiers’ Union, which does seem to have been associated with the Folkestone mutiny, and was itself connected to the left through its links with the newspaper, the Daily Herald. It is really worth a read: A2 and the Reds In Khaki

We took the accounts above from Andrew Rothstein’s book, ‘The Soldiers Strikes of 1919’.

We also hope to type up the full accounts of all the January 1919 protests soon…

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

An entry in the

2018 London Rebel History Calendar

Leave a comment