On 15 January 1645, Nicholas Tew, a stationer of Coleman Street in the City of London, was questioned by a Parliamentary Committee investigating an underground press used by civil war radicals and budding Leveller leaders John Lilburne & Richard Overton. Tew’s house had been raided in December 1644 by the Stationers’ Office, responsible for censorship and licensing of publications, who were hard at work repressing the numerous unlicensed presses that had sprung up and were busy spreading all manner of radical political and religious ideas. The English Civil War had begun as conflict between king and Parliament over constitutional questions, religious and economic conflict and the question of where power in the country was vested; but the moderate bourgeoisie and gentry of Parliament had opened a can of worms by appealing to the classes below them in the name of liberty. Whole new groupings were emerging calling for social change and freedom of religious worship, and the privations and sacrifice of the war had spurred thousands on to question why they were fighting for, and beginning to go beyond the limited liberty the victory over the king had won them. The Levellers were the most well known of the political movements that evolved from this ferment.

The son of a London gentleman, bound apprentice to the stationer Henry Bird in September 1629, and freed in October 1638, Tew had emerged from the radical wing of the Baptists; he is thought to have been a member of Thomas Lambe’s independent congregation, which was meeting at Whitechapel in March 1643, Tew was possibly ‘the Girdler at the exchange, who teacheth at Whitechapel at a chamber every sabboth day’). At some point around 1643, he was involved in a dust-up with a ‘malignant’ (pro-Royalist) fellow-stationer, Edward Dobson (printer of several anti-parliamentary tracts), who was nicked for beating Tew.

By 1644 Tew was working as a stationers or printer in Coleman Street, “London’s most notorious radical centre”, a narrow lane running up towards the City of London wall next to the Moor Gate, which opened onto Moorfields. Coleman Street’s tempestuous politics arose from both its position near the City’s edge, and the demographic of its residents (although interestingly, the original London Jewry ran from Cheapside, all the way north, across Lothbury and to Coleman Street. London’s first synagogue was located in neighbouring Ironmonger Lane. Is it possible that this influenced Coleman Street’s long history of religious non-conformism?). Filled with poor craftsmen, Coleman Street and the alleys and courts which branched off it were one of the most notorious centres of radicalism and religious non-conformism, from before the Civil War. Here radicalism and protests against authority had flourished since the 1620s at least; the five members of Parliament famously targeted for arrest by king Charles I in January 1642 were sheltered here, and Cromwell & the Puritan preacher Hugh Peter met regularly in the Star Inn; in 1645 women preached here, against all custom of the time, upsetting the established church hierarchies. The street and alleys teemed with radical congregations: in Bell Alley, off Coleman Street, was a noted centre of the most radical of the civil war religious sects. 1000s flocked here at times to hear radical preachers, including the Fifth Monarchist, John Goodwin, the ‘Red Dragon of Coleman Street’, and Thomas Lamb’s, who headed an Anabaptist congregation, of which Tew seems to have been a member. Lamb was soap-boiler, who preached the heresy that everyone was redeemed by Christ’s death, even pagans and Muslims. Later Fifth Monarchists plotted here against the Rump Parliament: Thomas Venner & other Fifth Monarchists preached in Swan Alley, from where they launched two attempts at insurrection, against Cromwell’s Protectorate, then against the restoration of king Charles II. Tew’s shop was in the heart of the swirling mix of radial religious and political debate which had both helped to give birth to the civil was and been encouraged and leavened by it. (Coleman Street would remain a centre for rebels until at least the 1780s, when Several Gordon Rioters were hanged here, probably as they lived here or emerged to riot from here.)

Tew had been called to answer questions about a tract distributed in December 1644; a single printed sheet, attacking the moderate Parliamentary generals, the Earls of Essex and Manchester, which was ‘scattered about ye streets in the night’, which accused the aristocratic leaders of a betrayal of the parliament and a fraud upon the troops, concluding: ‘Neither of them work, but make work; when they should do, they undo, and indeed to undo is all the mark they aime at. Do ye think greatness without goodness can ever thrive in excellent actions? No, honour without honesty stinks; away with’t: no more Lords and ye love me, they smell o’ the Court.’ Articulating the widespread suspicion that many of the leaders of both the army and Parliament were at best lukewarm about the war against the king, and possibly even in league with him or prepared to make a deal. (Suspicions to be revived and confirmed later in the decade).

An apprentice, George Jeffery, examined by the House of Lords, named preacher Thomas Lambe as one of the distributors of this sheet.’ (Lambe being the preached Tew was associated with) On 17 December, the House was told that the Stationers had found in Tew’s possession ‘divers scandalous books and pamphlets, and a letter for printing; the letter thereof is very like the letter of the libel against the peers’. He was arrested and examined by three Lords, but refused to answer; the committee recommended his committal ‘for his contempt, and that he may be forth-coming’ with information on ‘the authors, dispersers and printing of these books, and what he knows concerning the scandalous libel’.Tew refused to answer questions when hauled in front of Parliament’s Committee of Examinations; accordingly, on 26 December, Tew was ‘committed to the Fleet’ and justices were appointed to examine him. They eventually (on January 17th) extracted a confession from him, that a printing press had been brought to his house, and Richard Overton (who lodged in rooms in Tew’s house) and others he did not know had printed several items…

John Lilburne used the press at Tew’s to print an open letter to his former mentor, & now bitter opponent, the puritan William Prynne, calling for religious freedom of conscience.

Tew also admitted that another book of Lilburne’s, possibly his Answer to Nine Arguments, was printed on the press. But Tew refused or wasn’t able to say who had given him the manuscripts for printing, and he was sent back to his cell in the Fleet. Not till Monday 10 Feb, when Tew petitioned for release, was he bailed.

The same day, John Lilburne was also summoned to be examined by the Committee of Examinations, but walking in Moorfields before the hearing he was accidentally injured, when a pike was run into his eye, so his case was postponed… The seizure of the Leveller press housed at Tew’s shop did not silence them for long; radical bookseller William Larner set one up in his premises at Bishopsgate, which after searches by the authorities, later moved to Goodman’s Fields, Whitechapel.

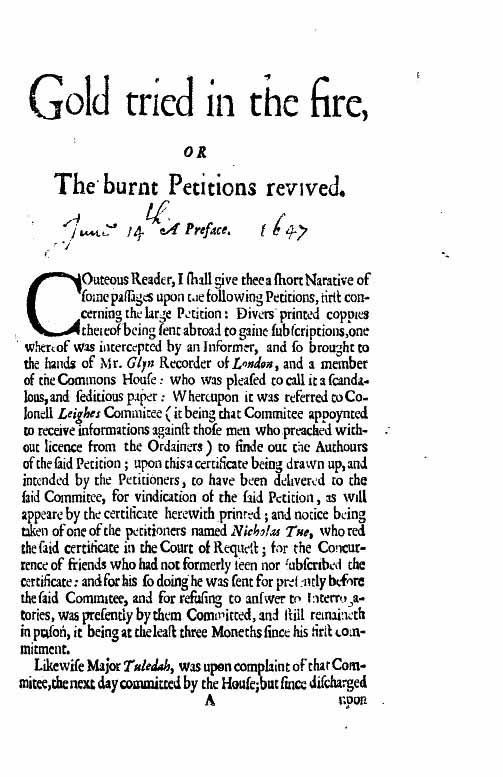

Nicholas Tew re-appears later, as an activist in the growing Leveller movement in 1647; an initiator, together with William Walwyn and others, of the ‘Large Petition’, a set of demands for constitutional and social reform, the most far-reaching yet articulated by the Levellers and New Model Army Agitators. The petition called for the abolition of tithes and monopolies, of unequal and unjust punishments, the banning of imprisonment for debt and harsh conditions and treatment in prisons, and pressed for the recognition of freedom of religious conscience, freedom of speech and the press, pegging back of the powers of the House of Lords and ending repression and persecution by the Presbyterian Parliament. The Levellers had developed petitioning as one of their main campaigning tools, and had recently managed to collect 10,000 signatures for one calling for the release of Lilburne and other imprisoned radicals who had been jailed by parliament for publishing ‘scandalous’ pamphlets, tracts calling for political reform and denouncing parliamentary repression and wavering in the cause that the civil war had been fought for.

This previous petition had been signed by thousands, despite active interference from some army leaders, and even from independent ministers who had previously been allies or supporters of Lilburne’s campaigns for change. The radicalisation of parts of the movement that had opposed king Charles was opening up splits in previous alliances, as Lilburne and others evolved programs that went beyond religious self-determination towards social change…

By this time Tew had been called to give evidence several times before the Committee of Examinations, and besides Lilburne was a known associate of men like William Browne, a Leveller bookseller, and Major Tulidah, a soldier thought to have been a ‘London agent’ for the Agitators, a connection between the radicals in the City of London and the army.

Besides his arrest in 1645, Tew had also been imprisoned again, ‘most illegally by the present Lord Mayor of London, fetched out of his shop and committed to Newgate, for having had in his custody one of the petitions promoted by the citizens of London. He was also to go to jail in 1647.

Tew was one of a crowd who marched in support of the minister Thomas Lambe, when he was summoned to interrogation by the Committee in March 1647, and was arrested while reading a statement aloud in the Court of requests responding to Parliamentary denunciation of the Large Petition as a seditious libel, and jailed in Westminster Prison. A disturbance followed in which Tulidah and others were dispersed by force. Tew refused to petition the House of Commons for his release and remained locked up, despite further petitions which called for his release as well as for recognition of the right to petition, and restriction of the powers of the reactionary parliamentary committees.

I don’t know what happened to Tew after this, though he may have continued to work as a stationer in Coleman Street till 1660 at least…

Worth reading: Free-Born John, The Biography of John Lilburne, Pauline Gregg.

and

The British Baptists and politics, 1603-1649, Stephen Wright.

And a good short look at Coleman Street

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

An entry in the

2017 London Rebel History Calendar – check it out online.

Leave a comment